The Griffins

The Giffins' Myths

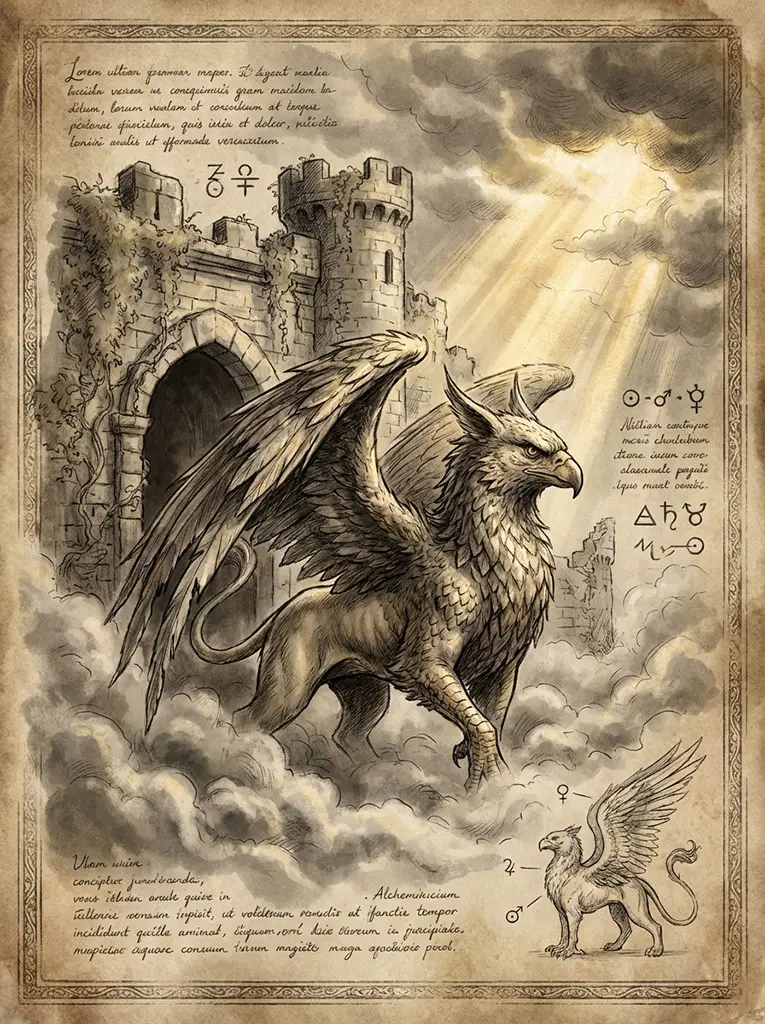

From the deserts of the ancient Near East to the pages of modern fantasy novels, the griffin has soared through human imagination as one of mythology’s most enduring hybrid creatures. With the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle, it unites the “kings” of land and sky into a single, awe‑inspiring guardian of treasure, power, and sacred spaces.

By tracing how the griffin shifts from temple guardian to fantasy mount, we can see how cultures repeatedly return to this creature when they need an image of strength that is not merely brutal, but noble, watchful, and bound to a higher duty.

The Loyal Guardian

The Role of the Griffin

Royal and Sacred Guardian

Historically, the griffin’s primary narrative role is that of guardian. It protects hoards of gold in Scythian mountains, shields royal tombs and temple precincts in Egypt and Persia, and stands watch at thresholds in art and architecture. This function maps easily onto political power: by placing griffins on thrones, gateways, and public monuments, rulers visually claim the same vigilant, unyielding protection for their realms.

Emblem of Rule and Identity

In heraldry, griffins appear rampant, segreant, passant, sejant, or couchant, with each posture conveying a slightly different nuance—aggressive readiness, calm authority, or watchful rest. They often adorn shields, helmets, banners, and crests of noble families, cities, and later universities or guilds, signaling leadership, noble lineage, and a commitment to defend one’s people.

Archetype of Structured Power

In myth and modern interpretation alike, the griffin represents ordered, disciplined power rather than chaotic ferocity. It does not roam aimlessly like some monsters; it has a clear duty—to guard—and is defined by its unwavering performance of that duty. In that sense, the griffin is often set alongside, and sometimes in contrast to, more ambivalent beasts like dragons or chimeras: where those embody dangerous chaos, the griffin stands for protective structure.

Genesis: Origins of the Griffin

The griffin (also spelled gryphon or gryphon) is a composite creature with the head, beak, and wings of an eagle and the body, tail, and hindquarters of a lion, combining the two supreme animals of sky and land into a single, hyper‑regal beast. Archaeological evidence places its origins in the ancient Near East, especially Elam, Mesopotamia, and Egypt, where griffin‑like forms appear in art as early as the 4th–3rd millennium BCE. From there the motif spreads across Syria and Anatolia into Minoan Crete, where vivid griffin frescoes decorate the palace of Knossos around 1500 BCE.

Some scholars suggest that the griffin legend may also have been reinforced by traders encountering protoceratops fossils on Central Asian trade routes, interpreting beak‑like skulls and quadruped skeletons as evidence of a lion‑bodied, bird‑headed beast guarding gold deposits. By the time Greek and later Roman writers adopt the griffin, it is already a well‑established “international” monster, equally at home in royal iconography, temple reliefs, and luxury goods.

Legends Across Cultures

Greek and Roman World

Greek authors systematize the griffin as a mythic race. Herodotus, Aeschylus, and later writers describe griffins inhabiting the mountains of Scythia, where they fiercely guard rich veins of gold against the one‑eyed Arimaspians, who wage constant war to steal their treasure. This motif (treasure‑guarding sky‑lions locked in endless battle) cements the griffin as a relentless sentinel over wealth and sacred resources.

In some later Greek and Hellenistic traditions, griffins pull the chariot of Apollo, the sun god, underscoring their solar and celestial associations. Romans inherit these images and reproduce griffins on mosaics, sarcophagi, and luxury objects, often as attendants of divine or imperial power.

Medieval Christendom and Bestiaries

In medieval Europe, the griffin migrates from classical myth into Christian symbolism and heraldry. Bestiaries describe it as so powerful it can carry an armored man on horseback through the air, and emphasize its ferocity and vigilance as a general moral emblem. Christian exegetes interpret the griffin’s dual nature, eagle above, lion below, as a symbol of Christ’s dual nature, divine and human, or as a guardian of the divine realm.

At the same time, griffins become prominent on coats of arms, seals, and architectural sculpture, often shown attacking dragons or standing sentinel on church façades and city gates. In some late medieval and Renaissance stories, griffins are said to lay eggs of agate in desert nests and to dwell in distant, unreachable lands, further reinforcing their aura of exoticism and dangerous majesty.

Near Eastern and Egyptian Traditions

In the ancient Near East, griffins appear as powerful guardians of palaces, temples, and royal tombs, often flanking thrones or sacred trees. In Egypt, griffin‑like figures are linked to the solar falcon god Horus; in some temple art, a falcon or hawk head merges with a lion’s body to express divine kingship and the fusion of sky power with terrestrial rule. Persian art develops a closely related hybrid known as the shirdal (“lion‑eagle”), functioning as a protective, royal emblem carved on palaces and elite tombs.

Power, Guardianship, and the In‑Between

Strength and Sovereignty

The lion contributes physical strength, courage, and royal status, while the eagle adds keen sight, authority from above, and solar or divine connotations. Together they form a super‑predator symbolizing dominion over both earth and sky.

Guardianship and Vigilance

Across Near Eastern, Greek, and medieval sources, griffins guard treasures, royal tombs, sacred spaces, or esoteric knowledge. In heraldry, they explicitly stand for watchfulness, courage, and the duty to protect—an embodiment of the ideal guardian who never sleeps on its post.

Justice, Loyalty, and Honor

Heraldic writers and emblem books treat the griffin as a symbol of just, disciplined power rather than brute violence. It implies martial courage tempered by responsibility, suitable for rulers, military orders, universities, and guilds that want to signal both strength and ethical duty.

Union of Earthly and Divine

Because it is half terrestrial beast, half aerial bird, the griffin occupies a liminal space between worlds. Medieval Christian authors exploit this to depict the griffin as a bridge between human and divine, or as a custodian of thresholds where the sacred must be defended from the profane

The Griffin in Modern Times and Geek Culture

Literature and Fantasy Media

Modern fantasy has enthusiastically adopted griffins as mounts, allies, and sometimes antagonists. C. S. Lewis features noble griffins fighting alongside Aslan in The Chronicles of Narnia, where they serve as airborne shock troops for the forces of good. In role‑playing games like Dungeons & Dragons, griffons are iconic flying creatures, often tamed as elite war‑mounts for knights and paladins, again emphasizing courage and air superiority.

Warcraft’s Alliance faction uses gryphons as signature aerial mounts, integrating the creature deeply into that universe’s visual identity and mapping it directly onto themes of honor and heroic defense. Other fantasy franchises, from The Spiderwick Chronicles to numerous tabletop games and novels, repeat the pattern: the griffin appears as a majestic, dangerous, but potentially loyal being whose alliance confers status and power on a worthy hero.

Film, Games, and Pop‑Geek Iconography

Video games, from MMOs to strategy titles, frequently use griffins as high‑tier units, flying cavalry, or boss guardians of important locations, mechanically mirroring their mythic role as protectors of treasure and chokepoints. Miniatures games and TCGs (trading card games) depict griffins with exaggerated wings and ornate armor, leaning into their function as symbols of elite, lawful power.