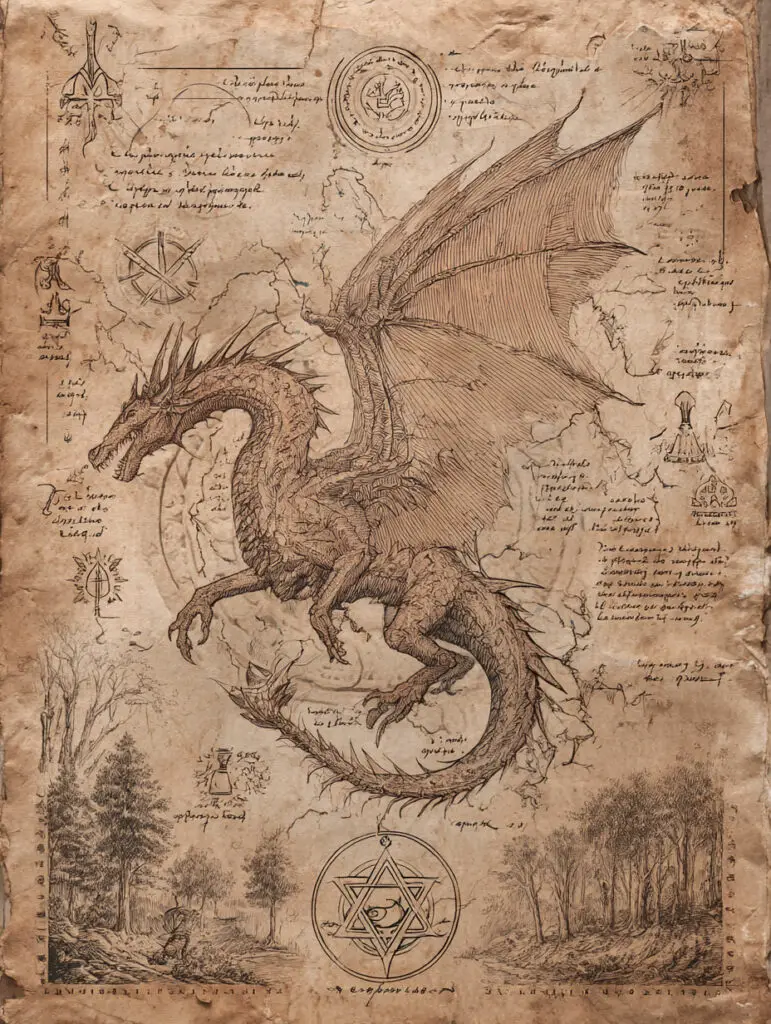

The Greatest Fantasy Novels with Dragons

For over a century, dragons in fantasy fiction have transformed from fire-breathing villains into wise friends and even cultural icons. Geek readers (especially those who love Dungeons & Dragons or Game of Thrones) have watched this evolution with delight. Each era’s storytellers put their own spin on these legendary beasts, reflecting changing attitudes and ensuring dragons remain as captivating as ever.

Early 1900s – Friendly Dragons in Children’s Literature

Kenneth Grahame (1859–1932) : best known for The Wind in the Willows. Introduced one of fiction’s first “good dragons.” His short story “The Reluctant Dragon” (1898) features a polite, poetry-loving dragon befriended by a young boy. In a gentle parody of the Saint George legend, the dragon refuses to fight; the boy and St. George stage a mock battle so the town will accept the pacifist beast. Grahame’s tale was warmly received for its humor and charm, later inspiring a 1941 Disney cartoon. It proved that dragons could be cute or comic, not just monsters.

Edith Nesbit (1858–1924), a pioneer of children’s fantasy. Her anthology The Book of Dragons (1900) collected eight whimsical dragon stories. Nesbit’s dragons range from tiny mischief-makers to friendly pets, delighting young readers. Grahame and Nesbit were among the first to show benign, even “good” dragons in print. Their success in the early 20th century opened the door for dragons to play nice, paving the way for more nuanced dragons in later fantasy.

1930s : Tolkien’s Smaug and the Return of the Fearsome Dragon

By the 1930s, fantasy for adults was emerging and with it came a return of the truly formidable dragon. J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973), an English professor and philologist, had adored mythical dragons since childhood. In The Hobbit (1937), he introduced Smaug, the archetypal greedy, fire-breathing wyrm. Tolkien’s dragons, inspired by the monsters of Norse and Anglo-Saxon legend (like Fáfnir and Beowulf’s dragon), are “majestic, fire-breathing, and terrifying”, the very opposite of Grahame’s chummy dragon. Smaug is ancient, cunning, and covetous of gold above all else. In the novel, the humble hobbit Bilbo Baggins steals a cup from Smaug’s hoard.

The Hobbit was an instant classic, praised for blending humor and mythology. Critics in 1937 noted that Tolkien wrote dragons with “fidelity” to myth, so much so that it felt like he had “studied trolls and dragons at first hand”. Young readers and adults alike were enthralled, and the book won a New York Herald Tribune prize for best juvenile fiction in 1938. Tolkien gave dragons like Smaug a rich personality and a voice, elevating them from mere beasts to intelligent foes. Yet he kept them fearsome, “a personification of malice, greed, [and] destruction,” as he described in his own criticism. Smaug’s legacy looms large: he set the template for fantasy dragons as sly, conversational villains, influencing countless games and novels (including D&D’s iconic dragon antagonists). Even decades later, when Smaug hit the big screen in The Hobbit films, he remained the gold standard (literally) of dragonkind.

1960s – Dragons Become Wise and Noble (Le Guin and McCaffrey)

It took until the late 1960s for authors to truly rehabilitate the dragon’s image for adult audiences. Two women led this charge, each reinventing dragons in landmark fantasy series. Anne McCaffrey (1926–2011), an American-Irish author, shattered conventions with Dragonriders of Pern. The first Pern stories, “Weyr Search” (Analog Magazine, 1967) and the novel Dragonflight (1968), introduced dragons as humanity’s allies. On the planet Pern, telepathic dragons bond for life with their human riders to defend against a deadly menace from the skies. McCaffrey was arguably “the first Western adult fiction writer” to show that a dragon “didn’t need to be evil just because it was a dragon”. Her dragons are empathetic, loyal creatures capable of deep friendship, a radical departure at the time. The trope of a psychic bond with a dragon became a staple in games and fiction after Pern’s popularity.

Almost simultaneously, Ursula K. Le Guin (1929–2018) offered a different take in her Earthsea saga. Le Guin, an American author known for literary fantasy and science fiction, made dragons wise, enigmatic elders. In A Wizard of Earthsea (1968) and its sequels, dragons are ancient and capricious beings who speak the True Language of magic. One famous Earthsea dragon, Kalessin, is as old as time, a creature of wisdom as much as fire.

The Earthsea books were critically acclaimed (the first won a 1969 Boston Globe Horn Book Award) and they’ve inspired generations of fantasy writers to treat dragons not just as beasts or pets, but as intelligent beings with dignity.

1980s – Dragons Everywhere: From RPGs to Epic Fantasy

By the 1980s, dragons had fully taken wing in pop culture. The influence of Dungeons & Dragons (1974) and its tie-in novels meant that every fantasy saga seemed to have a dragon or two. Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman’s Dragonlance Chronicles (1984–85), based on D&D game campaigns, brought full-color dragon warfare to the page, with evil chromatic dragons serving a Dark Queen and noble metallic dragons aiding heroes. These novels were massively popular among gamers and teens, though critically they were seen as light, trope-filled adventures. Still, the Dragonlance series influenced fantasy art and gaming, reinforcing many classic dragon tropes (ancient wyrms, dragon-gods, hoards of treasure) for a new generation. Meanwhile, other media expanded the dragon’s domain: in film, The NeverEnding Story (1984) gave us Falkor the luckdragon as a benevolent protector, and in anime, Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away (2001) would later feature a dragon spirit. Dragons were no longer rare in fiction… they were expected.

1990s – A Song of Ice and Fire: Dragons in a Gritty New Age

George R.R. Martin (b. 1948), an American novelist and former TV writer, took dragons into the grisly realm of political intrigue. In A Song of Ice and Fire (begun 1996 with A Game of Thrones), dragons return to a world that resembles the Wars of the Roses more than a fairy tale. The Targaryen dynasty’s three dragons – Drogon, Rhaegal, and Viserion – are born in a funeral pyre and grow into fearsome weapons of war. Martin’s dragons are formidable and untamable to most, yet they form a fierce bond with Daenerys Targaryen, who sees them as her “children.” In the books, as in the hit HBO adaptation, dragons symbolize the return of magic and the Targaryens’ divine right to rule. They are not cuddly companions (they incinerate enemies indiscriminately), but neither are they mindless beasts.

When A Game of Thrones was first published, it earned positive reviews but didn’t top bestseller lists. Over the next two decades, however, the series grew into a phenomenon. Critics praised Martin’s mature, unpredictable storytelling (Time famously dubbed him “the American Tolkien”), and by the 2010s the Game of Thrones TV series was a record-breaking hit.

2000s – A New Generation of Dragon Riders (Eragon and Temeraire)

In the 21st century, dragon stories have continued to thrive – often by blending older tropes with fresh settings. A notable early 2000s success was Christopher Paolini, who wrote Eragon (2002) as a teenager. Paolini openly drew on classic inspiration (a dose of Pern, a dash of Star Wars), crafting a straightforward hero’s journey about a farm boy who becomes a dragon rider. Eragon and his blue dragon Saphira captured young readers’ hearts. The novel was initially self-published, then picked up by Knopf in 2003 – and it soared up the charts. Eragon spent 121 weeks on the New York Times children’s bestseller listen and sold millions of copies worldwide.

Meanwhile, another author was putting a twist on dragon lore by mixing it with real history. Naomi Novik made a splash with His Majesty’s Dragon (2006), the first in her Temeraire series. Often pitched as “Patrick O’Brian with dragons,” the series is set during the Napoleonic Wars – but with an Aerial Corps of dragon-riding aviators fighting on all sides. Novik, a Polish-American writer and avid history buff, gave us Temeraire, a rare Chinese Celestial dragon who bonds with a British naval captain. This partnership, and the very idea of dragons as military assets, owes much to McCaffrey’s groundwork (indeed, Temeraire feels more like a descendant of Pern’s dragon queen Ramoth than of Tolkien’s Smaug)

2020s – Dragons in the Age of “Romantasy” (Fourth Wing and Beyond)

In the 2020s, dragons are still conquering bestseller lists – and now they’re doing it hand-in-hand with another trend: fantasy romance. Rebecca Yarros , previously known for military romance novels, took a bold leap into fantasy with Fourth Wing (2023). The novel—set in a war college where young cadets pair with dragons—reads like a blend of Pern’s rider bonds, The Hunger Games’ deadly school trials, and a spicy forbidden romance. Yarros’s protagonist Violet is a fragile bookworm forced to become a dragon rider, and she ends up bonded to not one but two powerful dragons. Fourth Wing struck a nerve (or lit a spark) with modern readers. It became a viral BookTok phenomenon and shot to #1 on the New York Times bestseller list, staying there for 18 weeks. Fourth Wing has been credited with helping popularize the emerging “romantasy” genre (romance-heavy fantasy).

Conclusion – Here Be Dragons, Forever

Over the past century, dragons in fantasy literature have morphed from menacing monsters into multi-faceted beings that can symbolize just about anything. Early writers used dragons as stock villains to be vanquished; later they became mentors, friends, even romantic partners. This evolution reflects a broader change in our culture – we’ve moved away from viewing the unknown as evil (the medieval view of “here be dragons”) toward seeing it as something to understand or even befriend. Dragons have come to represent many things: greed and chaos (Smaug guarding his hoard), the bond between human and nature (the dragon-riders of Pern), the wisdom of ancient knowledge (Earthsea’s sages of the wind), or the destructive power of technology and ambition (the dragons in Game of Thrones as weapons of mass destruction). They can be symbols of evil or hope, chaos or balance, depending on the tale.

What hasn’t changed is dragons’ ability to captivate us. Perhaps it’s the awe they inspire that makes dragons endlessly intriguing. We keep reinventing dragons in our books and media because they’re the ultimate fantasy mirror: reflecting our deepest fears, our highest aspirations, and our enduring love for adventure.